Long and Little Known: How Incoherent Statutes Harm Liberty & the Rule of Law

“It will be of little avail to the people that the laws are made by men

of their own choice if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so

incoherent that they cannot be understood . . . .”

—James Madison, Federalist 62

In support of the federal Constitution, James Madison explained that “It will be of little avail to the people that the laws are made by men of their own choice if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood.”1 Mr. Madison understood law “to be a rule of action,” and asked, “but how can that be a rule, which is little known, and less fixed?”2 Today, more than two centuries later, Mr. Madison’s warning has proven both prescient and forgotten. With federal bills and statutes droning on for hundreds and thousands of inscrutable pages of legal jargon, federal legislation has grown so voluminous that it cannot be read and so incoherent that it cannot be understood. Consequently, federal laws today are too often “little known” by the representatives who enact them and the people who must obey them.

Congress was not always so long-winded, of course. For much of the nation’s history, Congress followed the wisdom of Mr. Madison’s counsel and even laws of great significance were penned succinctly, able to be read and understood in the normal course by citizens and their elected representatives. A brief law, of course, may not necessarily be a good law, but history demonstrates that laws may be both significant and succinct.

The Judiciary Act of 1789, for example, established the judicial courts of the United States in 21 typed pages. 3 The act establishing a uniform rule of naturalization in 1790—of no small importance to a young nation of immigrants—took less than two pages of text.4 Congress repealed and replaced this Act in 1795, again requiring just two pages to do so. 5 As the nation grew exponentially through the 19th century, laws were passed accordingly, but even significant legislation like the National Banking Act of 1863 providing for and regulating a national currency took Congress 18 pages to articulate. 6 Similarly, the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 creating our modern federal reserve system required a mere 25 pages. 7 Monumental 20th century reforms like the Social Security Act of 1935 ushered in sweeping change with less than 30 pages of text, 8 and broad-based regulatory statutes like the Clean Air Act of 1963 ran just 10 pages, 9 while its younger cousin, the Clean Water Act of 1972, dribbled on for 88 pages. 10

Over time, however, Congress increasingly ignored Mr. Madison’s advice, so that today, and for several decades now, many federal laws routinely run for hundreds of pages. Federal law has expanded in size and scope, reaching virtually every facet of American life through laws that too often have exceeded 500 and even 1000 pages. Congress has grown fond of combining many different issues into oversized bills, shielding representatives from their constituents, and making it more difficult for officials and the public to fully appreciate what the bills contain. It is now not uncommon for Congress to consider consolidated spending or “omnibus appropriations” bills requiring thousands of pages that members openly acknowledge cannot possibly have been read or understood before votes were taken.

Over time, however, Congress increasingly ignored Mr. Madison’s advice, so that today, and for several decades now, many federal laws routinely run for hundreds of pages. Federal law has expanded in size and scope, reaching virtually every facet of American life through laws that too often have exceeded 500 and even 1000 pages. Congress has grown fond of combining many different issues into oversized bills, shielding representatives from their constituents, and making it more difficult for officials and the public to fully appreciate what the bills contain. It is now not uncommon for Congress to consider consolidated spending or “omnibus appropriations” bills requiring thousands of pages that members openly acknowledge cannot possibly have been read or understood before votes were taken.

The Cato Institute’s Timothy Lynch reminded Congress during congressional testimony in 2009:

There is precious little difference between a secret law and a published regulation that cannot be understood. History is filled with examples of oppressive governments that persecuted unpopular groups and innocent individuals by keeping the law’s requirements from the people. For example, the Roman emperor Caligula posted new laws high on the columns of buildings so that ordinary citizens could not study the laws. Such abominable policies were discarded during the Age of Enlightenment, and a new set of principles-known generally as the “rule of law” took hold. 11

That “rule of law” is threatened by voluminous and incoherent bills and statutes that breed ignorance and confusion among the people, confound their elected representatives, favor the few and not the many, sew seeds of public contempt for Congress, and undermine the people’s confidence in our constitutional order. It is time for political leaders to put the country before politics, and renounce the political gamesmanship that plagues our law and pollutes the lawmaking process.

I. LOST TRANSPARENCY: BREEDING IGNORANCE AND CONFUSION

Slate reported in 2009 that “major spending bills frequently run more than 1,000. This year’s stimulus bill was 1,100 pages. The climate bill that the House passed in June was 1,200 pages. Bill Clinton’s 1993 health care plan was famously 1,342 pages long. Budget bills can run even longer: In 2007, President Bush’s ran to 1,482 pages.” 12 The Slate article when on to note that “Over the last several decades, the  number of bills passed by Congress has declined: In 1948, Congress passed 906 bills. In 2006, it passed only 482. At the same time, the total number of pages of legislation has gone up from slightly more than 2,000 pages in 1948 to more than 7,000 pages in 2006. (The average bill length increased over the same period from 2.5 pages to 15.2 pages.)” 13 This means that more “law,” or “rule of action” is actually being passed by Congress in fewer and fewer individual, stand-alone statutes. Slate author, Christopher Beam, casually dismissed concerns raised by these massive legislative tomes; but such concerns should not be taken lightly.

number of bills passed by Congress has declined: In 1948, Congress passed 906 bills. In 2006, it passed only 482. At the same time, the total number of pages of legislation has gone up from slightly more than 2,000 pages in 1948 to more than 7,000 pages in 2006. (The average bill length increased over the same period from 2.5 pages to 15.2 pages.)” 13 This means that more “law,” or “rule of action” is actually being passed by Congress in fewer and fewer individual, stand-alone statutes. Slate author, Christopher Beam, casually dismissed concerns raised by these massive legislative tomes; but such concerns should not be taken lightly.

Without question, clear, concise laws of merely a few pages may infringe upon liberty or otherwise prove to be “bad law.” The substance and requirements of any law ultimately determine its merit. The same harmful effects of a single, incoherent statute of 1000 pages, for example, may be achieved by five clear laws of 200 pages, or ten 100-page laws. But shorter, more concise bills and statutes have the virtue and advantage of transparency. They quite simply are more capable of being read and understood by the representatives who pass them and the citizens they govern. With such transparency, clear, concise statutes permit the people to hold their representatives more readily accountable for the law’s consequences—whether good or bad. By contrast, longer, less coherent laws spanning hundreds if not thousands of pages tend to obscure their full content by their density, sheer length, or both, making the law—as Mr. Madison said—“so voluminous that they cannot be read” and therefore harder for the governed to obey.

Then-Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi, epitomized this truth with her infamous statement during the debates in 2010 over President Obama’s 906-page Affordable Care Act14 when she exclaimed: “We have to pass the bill so that you can find out what is in it, away from the fog of the controversy.” 15 Ms. Pelosi’s telling remark revealed the dark truth of the matter—that Congress was indeed voting on and passing laws that its members have not even read, much less understood. Of course, this was no obscure, small piece of legislation likely to affect only a few congressmen and their constituents. The Affordable Care Act would fundamentally change the nation’s healthcare system, leave an indelible mark on 17% of the economy, and was hotly contested in the daily headlines for months before Ms. Pelosi’s remarkable confession that Congress would need to pass the bill before Congress could know what it said.

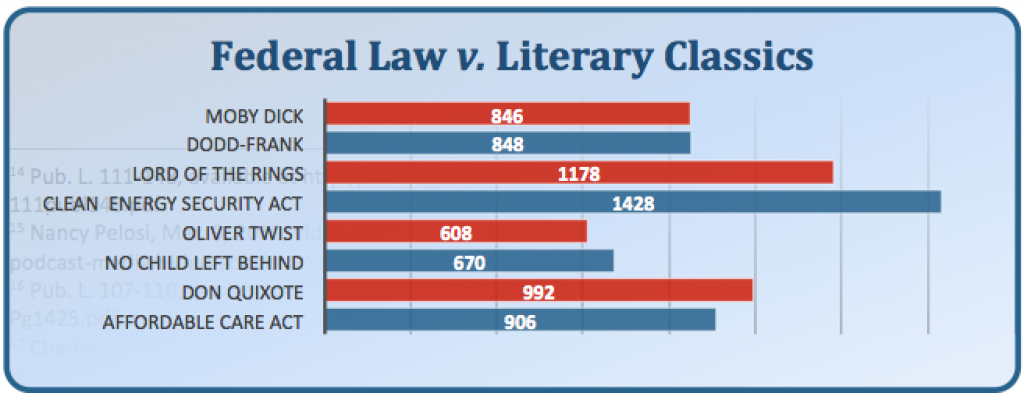

Unfortunately, the Affordable Care Act is not the only epic piece of statutory literature passed by Congress in the new millennium. To put the reading required for a few of Congress’ more recent laws into perspective, consider that The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, instructing the reader for 670 pages, 16 was roughly the length of Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist. 17 The Farm Security and Rural Reinvestment Act of 2002 with its 407 pages18 was nearly as long as John Steinbeck’s agrarian classic The Grapes of Wrath. 19 To read the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement Act of 2003 at 415 pages20 would require more commitment and prove far less rewarding than sitting down with The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. 21 In 2009, the House of Representatives managed to pass—although surely not read—the American Clean Energy Security Act. 22 With its 1428 pages, the Act exceeded all three volumes of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings combined by 250 pages. 23

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 is a whale of a law at 848 pages24 and roughly the size of the great American novel, Moby Dick. 25 And, for what it may be worth, the 906-page version of the Affordable Care Act that passed Congress was just slightly shorter than the fanciful quest of Don Quixote. 26 With page-counts like these, members of Congress (even with staff) cannot possibly read and comprehend all that these laws contain. Instead, as Ms. Pelosi confessed, they must pass the bills in order that they, too, might discover what they say.

Voluminous, incoherent laws erode liberty and self-rule by creating legal confusion and breeding ignorance among elected officials and citizens alike. Congressional efforts to pass the Affordable Care Act provide yet another infamous example. Speaking of the confusing and incoherent language used in drafting the Affordable Care Act, Jonathan Gruber, one of the Act’s chief legislative architects explained that if Congress had made the bills’ financing and spending provisions transparent, the bill would have failed to pass.

According to Mr. Gruber, “if you had a law which said that healthy people are going to pay in—you made explicit that healthy people pay in and sick people get money, it would not have passed, okay. Lack of transparency is a huge political advantage. And basically, call it the stupidity of the American voter or whatever, but basically that was really, really critical for the thing to pass . . . . Look, I wish Mark [Pauly] was right that we could make it all transparent, but I’d rather  have this law than not.” 27 As Avik Roy of Forbes later explained, Mr. Gruber essentially admitted what many of the Act’s critics argued from the beginning: “It’s that the law’s complex system of insurance regulation is a way of concealing from voters what Obamacare really is: a huge redistribution of wealth from the young and healthy to the old and unhealthy. In the video, Gruber points out that if Democrats had been honest about these facts, and that the law’s individual mandate is in effect a major tax hike, Obamacare would never have passed Congress.” 28

have this law than not.” 27 As Avik Roy of Forbes later explained, Mr. Gruber essentially admitted what many of the Act’s critics argued from the beginning: “It’s that the law’s complex system of insurance regulation is a way of concealing from voters what Obamacare really is: a huge redistribution of wealth from the young and healthy to the old and unhealthy. In the video, Gruber points out that if Democrats had been honest about these facts, and that the law’s individual mandate is in effect a major tax hike, Obamacare would never have passed Congress.” 28

Mr. Gruber’s admission regarding Obamacare is certainly alarming, but Democrats are not alone in their efforts to conceal or bury legislative language in bills in order to avoid detection and defeat. As The New York Times reported, “A once-popular bill to help victims of sex trafficking was derailed in the Senate recently when Democrats discovered that language restricting funding for abortions was in the bill — sneaked in, they charged, by Republicans.” 29 The Senate ultimately passed the Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act with some abortion funding restrictions, but the efforts used at first to conceal the full effect of the bill suggest that both political parties know how to play “hide-the-ball.” Explaining the Republicans’ failed attempt, The New York Times columnist, Derek Willis, opined:

The sex-trafficking bill’s offending language isn’t exactly transparent; it doesn’t mention abortion at all. It says, if you can parse the legalese: ‘Amounts in the [Domestic Trafficking Victims’] Fund, or otherwise transferred from the Fund, shall be subject to the limitations on the use or expending of amounts described in sections 506 and 507 of division H of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2014 . . . to the same extent as if amounts in the Fund were funds appropriated under division H of such Act.’ The “limitations” referred to in the bill say that money can’t be spent “for any abortion” except in cases of incest or rape or “for health benefits coverage that includes coverage of abortion.” But in order to know that, a reader of the bill would have to know what was in part of the law passed in January 2014 or know what search keywords to use in those sections . . . . 30

Stand-alone, issue-related statutes like the Affordable Care Act or the Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act are not the only culprits here. Federal spending or “appropriations” bills provide notorious examples of congressional ignorance and confusion created by legislative chicanery, “earmark” spending, consolidated appropriations bills, and last-minute voting that forces members to vote on bills before given the chance to read them.

Since the 1980s, Congress has increasingly relied on “omnibus” appropriations bills that consolidate at least a dozen smaller spending bills into one colossal piece of legislation authorizing the government to spend money. Writing for the National Priorities Project, Jasmine Tucker has explained: “An omnibus spending bill packages together all 12 of the appropriations bills that are supposed to be passed individually into one large spending bill, worth billions or even trillions of dollars. In addition to these 12 appropriations bills, omnibus spending bills often contain many unrelated pieces of legislation.” 31 Not surprisingly, omnibus appropriations bills often run well over 1000 pages. Ms. Tucker noted matter-of-factly, “Because of their size, omnibus bills usually only receive a cursory look by the committees charged with reviewing them. And despite a lack of understanding of what is in an omnibus, they are not usually subject to much debate . . . .” 32

These mammoth bills prove far too tempting for Congress and its staff to resist playing legislative games. In 2007, the congressional watchdog Citizens Against Government Waste recounted the following discouraging stories of legislative corruption and abuse:

In 1997, Jason Alderman, a staffer for the late Rep. Sidney Yates (D-Ill.), had an altercation with a policeman after being stopped for walking his dog without a leash in Meridian Hill Park in Washington, D.C. Alderman later got language added to a House appropriations bill ordering the National Park Service to build a dog run at the park “as expeditiously as possible.” Rep. Yates was unaware of the earmark until it appeared in a column by the late journalist . . . Jack Anderson.

More recently, a staffer held up passage of the fiscal 2005 Omnibus Appropriations Act after he added an obscure line to the 3,000-page bill that would give the chairmen of the Appropriations Committees and their staff assistants the authority to access the income tax returns of any American. The language was discovered only hours before the original vote was scheduled and Republican leaders had to convene a special session to remove the provision.33

Of course, congressional staffers are not the only ones on Capitol Hill capable of these tactics. The confusion created by the sheer magnitude of some omnibus appropriations bills have historically led to members of Congress surprising each other with hidden pieces of “pork-barrel” spending that few members ever realized were included in the bill. Members of Congress quite literally vote to authorize spending taxpayer dollars on items and projects and services without a full appreciation for what they are even authorizing. Daniel Greenberg, in his book Science, Money, and Politics: Political Triumph and Ethical Erosion, recalls Senator John McCain’s outrage after learning about the last-minute “pork” that his colleagues had secretly squeezed into the bill “behind closed doors” just before the vote.

Of course, congressional staffers are not the only ones on Capitol Hill capable of these tactics. The confusion created by the sheer magnitude of some omnibus appropriations bills have historically led to members of Congress surprising each other with hidden pieces of “pork-barrel” spending that few members ever realized were included in the bill. Members of Congress quite literally vote to authorize spending taxpayer dollars on items and projects and services without a full appreciation for what they are even authorizing. Daniel Greenberg, in his book Science, Money, and Politics: Political Triumph and Ethical Erosion, recalls Senator John McCain’s outrage after learning about the last-minute “pork” that his colleagues had secretly squeezed into the bill “behind closed doors” just before the vote.

In October 1998, late with its work and eager to get off to the election campaign, the 105th Congress hurriedly combined all pending money legislation into a $500 billion-plus Omnibus Appropriations bill, covering nearly four thousand densely printed pages. In the light of day, the bill was found to be loaded with a plenitude of pork, possibly a record-breaking quantity, though counting is difficult in the dimly lit chambers of earmark politics. A review by Senator John McCain (R-Ariz.) cited several thousand appropriations that he described as “unauthorized” or outside “the normal competitive award process.” The grand total of earmarks was later tabulated at $528 million, en route to $797 million in 1999. . . . In the tradition of pork-barrel appropriations, McCain pointed out, the earmarks had not been debated or even made available to scrutiny prior to passage: “They were simply added, behind closed doors, to this massive, non-amendable omnibus bill.”34

Regrettably, Congress did not learn from the missteps of 1998 or heed Mr. McCain’s concern. Writing more recently of the Senate’s version of the fiscal year 2011 omnibus appropriations bill, Brian Riedl of The Daily Signal lamented: “In a single 1,924-page bill—which was crafted in secret and will be voted on before anyone has read it fully—Congress is set to spend a staggering $1.1 trillion on discretionary programs for fiscal year (FY) 2011, plus an additional $160 billion in emergency war spending.”35 Of course, one solution to the difficulties created by oversized omnibus appropriations bills would be for Congress to return to considering and voting on the 12 or so individual appropriations individually. Such bills may not be “short,” but would certainly provide a manageable way for members of Congress to read and debate the merits of the individual appropriations one bite at a time, rather than trying to swallow all 12 of them whole.

II. LOSING LIBERTY: LAWS FAVORING THE FEW, NOT THE MANY

When the true substance of the laws are concealed within hundreds of pages of dense “legalese,” such a “lack of transparency”—as Mr. Gruber called it—preys upon the very ignorance and confusion that it creates. That same ignorance and confusion ultimately benefits those with the time and inclination to parse the meaning of the incoherent tomes considered or enacted by Congress. Constitutional architect, James Madison, warned of this too, observing that “Every new regulation concerning commerce or revenue, or in any manner affecting the value of the different species of property, presents a new harvest to those who watch the change, and can trace its consequences; a harvest, reared not by themselves, but by the toils and cares of the great body of their fellow-citizens. This is a state of things in which it may be said with some truth that laws are made for the few, not for the many.” 36 That is, the labyrinth of new, complicated rules and regulations benefits those who find ways to use those new rules to their advantage in the marketplace. But in that way, the laws, as Mr. Madison wrote, are “made for the few, not for the many.”

Relatedly, laws written in this fashion and with this purpose may not  in fact be written for the public at all. Just as Mr. Gruber so candidly admitted that a designed “lack of transparency” would conceal the real meaning and effects of the Affordable Care Act, so too are some laws written largely for regulators and bureaucrats. According to corporate law professor, Jonathan Macey of Yale Law School, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform statute is one example of just such a law. “Laws classically provide people with rules,” Macey said. “Dodd-Frank is not directed at people. It is an outline directed at bureaucrats and it instructs them to make still more regulations and to create more bureaucracies.” 37

in fact be written for the public at all. Just as Mr. Gruber so candidly admitted that a designed “lack of transparency” would conceal the real meaning and effects of the Affordable Care Act, so too are some laws written largely for regulators and bureaucrats. According to corporate law professor, Jonathan Macey of Yale Law School, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform statute is one example of just such a law. “Laws classically provide people with rules,” Macey said. “Dodd-Frank is not directed at people. It is an outline directed at bureaucrats and it instructs them to make still more regulations and to create more bureaucracies.” 37

The Dodd-Frank “outline” runs on in densely-packed legalese for nearly 850 pages, hiding and obscuring any number of regulatory anomalies and requirements from the public and their elected representatives who lacked the time and inclination to parse its meaning. By contrast, the Banking Act of 1933, commonly known as the Glass-Steagall Act, substantially reformed America’s banking system during the Great Depression and informed the public of the new federal rules in under 40 pages. 38 Both Dodd-Frank and Glass-Steagall enacted sweeping reforms to banking—for good or ill—but one provided Congress and the public with a concise, coherent, understandable rule; the other, more recent “outline” about as long as Moby Dick, creates a bramble of new, often redundant rules covering issues related to “veterans, students, the elderly, minorities, investor advocacy and education, whistle-blowers, credit-rating agencies, municipal securities, the entire commodity supply chain of industrial companies, and more.” 39

In 2012, The Economist warned that poorly drafted, incoherent provisions of Dodd-Frank give federal regulators “the power to regulate more intrusively and to make arbitrary or capricious rulings. The lack of clarity which follows from the sheer complexity of the scheme will sometimes, perhaps often, provide cover for such capriciousness.” 40 Mr. Lynch of The Cato Institute voiced similar concerns in his testimony before Congress regarding other rampant and confusing regulatory control exercised by federal agencies and prosecutors due to the size, scope, and uncertainty of federal law. As Mr. Lynch noted, “the Environmental Protection Agency received so many queries about the meaning of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act that it set up a special hotline for questions. Note, however, that the ‘EPA itself does not guarantee that its answers are correct, and reliance on wrong information given over the RCRA hotline is no defense to an enforcement action.’” 41 He went on to inform congressional leaders that “the situation is so bad that even many prosecutors are acknowledging that there is simply too much uncertainty in criminal law. Former Massachusetts Attorney General Scott Harshbarger concedes, ‘One thing we haven’t done well in government is make it very clear, with bright lines, what kinds of activity will subject you to . . . criminal or civil prosecution.’” 42

Such uncertainty and confusion is not synonymous with liberty or a free people, and further confirms Mr. Madison’s warning that rules must be “known” and “fixed” in order to function properly as just laws. Requiring untenable interpretations from lawyers, bureaucrats, and regulators who have poured over the minutia of voluminous, incoherent statutes in order to abide by the law means that the laws are not for the many, but benefit only the few. As Mr. Madison forewarned, they “present[] a new harvest to those who watch the change, and can trace its consequences; a harvest, reared not by themselves, but by the toils and cares of the great body of their fellow-citizens.” 43

III. LOSING THE LEGISLATURE: HOLDING CONGRESS IN CONTEMPT

Having been told by Congress and the President for months before the Affordable Care Act’s passage that “if you like your healthcare insurance plan you can keep it,” much of the public was understandably outraged to later learn that the law in fact would strip some Americans of their insurance plans that did not meet the Act’s new requirements. Some who lost their preferred insurance coverage may have wondered whether this was what Ms. Pelosi meant when she cried that Congress needed to pass the bill in order to know what it really contained. No one likes to be ambushed, and learning about the negative effects of a bill only after it becomes law, or discovering that Congress quietly slipped hundreds of millions of dollars of “pork-barrel” spending into an appropriations bill without debate, breeds an unhealthy contempt for Congress and the legislative process.

Unfortunately, voluminous and incoherent bills presented to Congress and ultimately the people foster such public contempt, and simultaneously make it more difficult to hold the members of Congress accountable. Epic bills with several (sometimes competing) intertwined interests sandwiched together in jumbo-sized omnibus legislation makes it more difficult for the people to hold their representatives accountable for their votes. Instead of casting votes on discrete, singular statutes that will have an identifiable effect on their constituents, members of Congress obscure the true nature of their legislative votes by combining so many issues—related and unrelated—into a single bill that it becomes nearly impossible to know which of the issues in a given bill the elected member actually supported. Mr. Gruber’s assessment of the “lack of transparency” in the legislative process appears all too accurate.

Polling data and public surveys confirm the low regard that Americans across the political spectrum have for Congress. CNN reported bipartisan contempt for Congress in 2013, noting that “disdain for Washington is . . . bipartisan. Republicans give Congress a 9% approval rating, compared to 8% among independents and 10% among Democrats.” 44 More recently, Gallup polling revealed that whether Republican or Democrat “Americans’ job approval rating for Congress averaged 15% in 2014, close to the record-low yearly average of 14% found last year. The highest yearly average was measured in 2001, at 56%. Yearly averages haven’t exceeded 20% in the past five years, as well as in six of the past seven years.” 45 In August 2014, three months before the November midterm election, U.S. News & World Report reported on Gallup data finding: “An overwhelming majority of Americans surveyed, more than 80 percent, said most members of Congress don’t deserve re-election. If the trend continues, the willingness to re-elect members of Congress will be the lowest on record in a midterm election year. . . . As a result of the extreme dislike of Congress as a whole, the gap between willingness to re-elect local members versus most members of Congress is the widest in Gallup’s history – 31 percentage points.” 46

Polling data and public surveys confirm the low regard that Americans across the political spectrum have for Congress. CNN reported bipartisan contempt for Congress in 2013, noting that “disdain for Washington is . . . bipartisan. Republicans give Congress a 9% approval rating, compared to 8% among independents and 10% among Democrats.” 44 More recently, Gallup polling revealed that whether Republican or Democrat “Americans’ job approval rating for Congress averaged 15% in 2014, close to the record-low yearly average of 14% found last year. The highest yearly average was measured in 2001, at 56%. Yearly averages haven’t exceeded 20% in the past five years, as well as in six of the past seven years.” 45 In August 2014, three months before the November midterm election, U.S. News & World Report reported on Gallup data finding: “An overwhelming majority of Americans surveyed, more than 80 percent, said most members of Congress don’t deserve re-election. If the trend continues, the willingness to re-elect members of Congress will be the lowest on record in a midterm election year. . . . As a result of the extreme dislike of Congress as a whole, the gap between willingness to re-elect local members versus most members of Congress is the widest in Gallup’s history – 31 percentage points.” 46

Specific reasons for the public’s contempt are undoubtedly complex and varied, but hiding the cost of rampant federal spending through omnibus appropriations packages, obscuring the true nature of laws through manipulative legislative tactics, and writing rules that only regulators and bureaucrats can decipher, do not bolster confidence in Congress, they undermine it. William Galston, a Senior Fellow at The Brookings Institute, observed days before the 2014 election that behind the specific complaints with Congress “is a general withdrawal of public trust and confidence in our governing institutions. The most recent Politico survey found only 36% of Americans expressing confidence that the U.S. is well positioned to meet its economic and natural security challenges. 64% report feeling that right now, things are out of control.” 47 Mr. Galston went on to explain that “Government provides security, not only by protecting against physical danger, but also by providing reassurance that it is competent and confident about our collective ability to master the challenges we confront. By that standard, today’s elected officials have failed miserably.” 48 Sensing and sharing the public’s disgust with Congress, former House Majority Leader Eric Cantor told NPR in 2011, “Washington needs to stop adding confusion and more uncertainty to people’s lives.” 49 Confusion and uncertainty, of course, are two primary by-products of Congress enacting laws so long that no one can read them, and so incoherent that no one understands them.

As Congress forfeits the confidence of the people, it undermines its own rightful constitutional authority and purpose. Congress derives its authority from the people. It is the most representative of the three federal branches, and in that respect helps to ensure that the constitutional “rule of law” remains “by the people and for the people.” Mr. Madison extolled in The Federalist No. 49, “the people are the only legitimate fountain of power, and it is from them that the constitutional charter, under which the several branches of government hold their power, is derived . . . .” 50 But that “constitutional charter” and representative rule of law begin to erode as elected leaders in the House and Senate insulate themselves from the will the people—making themselves less accountable—either by abdicating their lawmaking responsibilities to the executive and judicial branches, failing to address the concerns of their constituents with clear legislative solutions, or surprising and confusing the public with laws that can be “little known” and less understood. Writing of the legislative branch in The Federalist No. 52, Mr. Madison reminded his audience that because “it is essential to liberty that the government in general should have a common interest with the people, so it is particularly essential that the branch of it under consideration should have an immediate dependence on, and an intimate sympathy with, the people.” 51

Unfortunately, as Congress finds ways through legislative gimmickry and “little known” laws to make its members less accountable to, dependent on, and in sympathy with the people, it becomes less representative of the people, and sacrifices its rightful function in the “constitutional charter.” Such a sacrifice imperils our individual liberties as protected by our nation’s republican constitutional order.

CONCLUSION

Long and incoherent legislation undermines our republican, constitutional form of government and the virtues gained by laws “made by men of their own choice.” For decades Congress has used manipulative tactics to hide the full effects of the law from the public and even from other members of the representative branches. The American people deserve better, and it is time for their leaders to put the good of the country before politics and return to the self-government principles our founders believed in.

With a few commonsense reforms Congress can again fulfill its constitutional obligation to represent the people. Representatives should proactively reduce and limit the length of the bills they consider and the laws they enact. Each bill should be concise and focused on one issue for consideration, allowing members of Congress and the public to better appreciate and understand the full meaning and potential effects of the law. Omnibus appropriations bills likewise should be dissolved and appropriations bills should once again present funding decisions on only the most inter-related programs and departments. To help prevent last-minute spending from being added to appropriations, or eleventh-hour amendments changing bills with little or no debate, Congress should vote on bills only after all members have been given a reasonable amount of time to read, consider, and debate the legislation. By rule, bills should be presented to members of Congress in final, unamendable form several days before votes may be taken. Shorter, readable bills should be crafted with clear, transparent language that avoids legalese and are written for the people that they will govern, not the bureaucrats that will apply them.

The laws of a free society should not be “little known” or “less understood.” The people—from whom the legitimate power to govern is derived—should know and understand that laws that govern them and the process by which those laws are determined. The size and scope of too much of our federal legislation has made such knowledge all but impossible, and has thereby threatened the representative fabric of our constitutional framework and the liberties enjoyed by a free republic.

by

Janine Turner & Nathaniel Stewart

A Publication of Constituting America

[1] James Madison, The Federalist 62 (Rossiter ed., 381).

2 Id.

3 See Judiciary Act of 1789, 1 Stat. 73, available at http://legisworks.org/sal/1/stats/STATUTE-1-Pg73.pdf.

4 1 Stat. 103, available at http://legisworks.org/sal/1/stats/STATUTE-1-Pg103.pdf.

5 See The Naturalization Act of 1795, 1 Stat. 414, available at http://legisworks.org/sal/1/stats/STATUTE-1-Pg414a.pdf.

6 See The National Banking Act of 1863, 12 Stat. 665, available at http://legisworks.org/sal/12/stats/STATUTE-12-Pg665.pdf.

7 See The Federal Reserve Act, Pub. L. 63-43, available at http://www.legisworks.org/congress/63/publaw-43.pdf.

8 See The Social Security Act of 1935, Pub. L. 74-271, available at http://www.legisworks.org/congress/74/publaw-271.pdf.

9 See The Clean Air Act of 1963, Pub. L. 88-206, available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-77/pdf/STATUTE-77-Pg392.pdf.

10 See The Clean Water Act of 1972, Pub. L. 92-500, available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-86/pdf/STATUTE-86-Pg816.pdf.

11 Timothy Lynch, “Over-Criminalization of Conduct/Over-Federalization of Criminal Law,” Testimony before Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security, Judiciary Committee, U.S. House of Representatives, July 22, 2009.

12 Christopher Beam, “Paper Weight,” Slate, Aug. 20, 2009.

13 Id.

14 Pub. L. 111-148, available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf.

15 Nancy Pelosi, Mar. 9, 2010, video available at http://www.intellectualtakeout.org/library/video-podcast-media/video-speaker-nancy-pelosi-we-have-pass-health-care-bill-so-you-can-find-out-whats-it.

16 Pub. L. 107-110, available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-115/pdf/STATUTE-115-Pg1425.pdf.

17 Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist (Penguin Classics) (2003) (608 pages).

18 Pub. L. 107-171, available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-116/pdf/STATUTE-116-Pg134.pdf.

19 John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath, (Penguin Classics) (2006) (464 pages).

20 Pub. L. 108-173, available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-117/pdf/STATUTE-117-Pg2066.pdf.

21 Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, (Penguin Classics) (2002) (368 pages).

22 H.R. 2454, available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-111hr2454pcs/pdf/BILLS-111hr2454pcs.pdf.

23 J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: 50th Anniversary, (One Vol. Ed.) (Mariner Books) (2005) (1178 pages).

24 Pub. L. 111-203, available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ203/pdf/PLAW-111publ203.pdf.

25 Herman Melville, Moby Dick (Amereon Ltd.) (2003) (846 pages).

26 Miguel De Cervantes, Don Quixote (translated by Edith Grossman) (Harper Perennial) (2005) (992 pages).

27 Avik Roy, “ACA Architect: ‘The Stupidity of the American Voter’ Led Us to Hide Obamacare’s True Costs from the Public,” Forbes, Nov. 10, 2014.

28 Id.

29 Derek Willis, “How to Avoid the Sex-Trafficking Bill’s ‘Surprise’,” The N.Y. Times, Mar. 24, 2015, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/25/upshot/how-to-avoid-the-sex-trafficking-bills-surprise.html?_r=0&abt=0002&abg=0.

30 Id.

31 Jasmine Tucker, “What Is an Omnibus?,” Jan. 14, 2014, National Priorities Project, available at https://www.nationalpriorities.org/blog/2014/01/14/what-omnibus/.

32 Id.

33 Tom Finnigan, “All About Pork: The Abuse of Earmarks and the Needed Reforms,” Mar. 7, 2007 (emphasis added), available at http://cagw.org/sites/default/files/pdf/2007/all_about_pork_2007_final.pdf.

34 Daniel S. Greenberg, Science, Money, and Politics: Political Triumph and Ethical Erosion, 186 (Univ. of Chicago Press) (2003).

35 Brian Riedl, “Senate Omnibus Bill: Nearly 2,000 Pages of Runaway Spending and Pork,” The Daily Signal, Dec. 15, 2010, available at http://dailysignal.com/2010/12/15/senate-omnibus-bill-nearly-2000-pages-of-runaway-spending-and-pork/.

36 James Madison, The Federalist 62 (Rossiter ed., 381).

37 See “The Dodd Frank Act: Too Big Not to Fail,” The Economist, Feb. 18, 2012, available at

38 See The Banking Act of 1933, Pub. L. 73-66, available at https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/scribd/?title_id=991&filepath=/docs/historical/congressional/1933_bankingact_publiclaw66.pdf#scribd-open.

39 “The Dodd Frank Act: Too Big Not to Fail,” The Economist, Feb. 18, 2012.

40 Id.

41 Timothy Lynch, “Over-Criminalization of Conduct/Over-Federalization of Criminal Law,” Testimony before Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security, Judiciary Committee, U.S. House of Representatives, July 22, 2009.

42 Id.

43 James Madison, The Federalist 62 (Rossiter ed., 381).

44 Dan Merica, “CNN Poll: Disapproval of Congress at Historic High,” Nov. 12, 2013, available at http://politicalticker.blogs.cnn.com/2013/11/12/poll-disapproval-of-congress-at-historic-high/.

45 Rebecca Riffkin, “2014 U.S. Approval of Congress Remains Near All-Time Low,” available at http://www.gallup.com/poll/180113/2014-approval-congress-remains-near-time-low.aspx.

46 Lindsey Cook, “Americans Still Hate Congress,” U.S. News & World Report, Aug. 18, 2014, available at http://www.usnews.com/news/blogs/data-mine/2014/08/18/americans-still-hate-congress.

47 William A. Galston, “2014 Midterms: Voters Head to the Polls Frustrated and Angry at Congress, President,” Oct. 27, 2014, available at http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/fixgov/posts/2014/10/27-2014-midterms-public-opinion-galston.

48 Id.

49 See Scott Neuman, “Congress Really Is As Bad As You Think, Scholars Say,” Dec. 27, 2011, available at http://www.npr.org/2011/12/27/144319863/congress-really-is-as-bad-as-you-think-scholars-say.

50 James Madison, The Federalist 49 (Rossiter ed., 313).

51 James Madison, The Federalist 52 (Rossiter ed., 327).

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!